Early Life and Education

Kwame Nkrumah was born as Francis Nwia-Kofi Ngonloma on September 21, 1909, in Nkroful, a small village in the Western Region of the British-occupied Gold Coast (now Ghana). He was born to a poor but proud family of the Nzema ethnic group. His mother, Elizabeth Nyaniba, played a significant role in nurturing him, while his absent father’s lack of presence left him dependent on his maternal family.

Despite his humble beginnings, Nkrumah’s intellectual potential stood out early in life. He attended elementary school in his hometown before earning a scholarship to the Achimota College in Accra. Achimota College was the premier institution for higher education in the Gold Coast at the time, and it was here that Nkrumah began to develop his interest in anti-colonial politics. Achimota’s curriculum stressed practical and intellectual engagement with Africa’s socio-political realities. Nkrumah graduated in 1930 and briefly worked as a teacher, but it was not long before he yearned for broader horizons.

In 1935, Kwame Nkrumah traveled to the United States to further his studies. He enrolled at Lincoln University in Pennsylvania, where he obtained a Bachelor of Arts degree in economics and sociology. He later earned another bachelor’s degree in theology and pursued graduate studies in philosophy and education at the University of Pennsylvania. His exposure to American society helped shape his early political thinking. While in the United States, he encountered racial discrimination, a bitter precursor to his lifelong fight against oppression. During this time, Nkrumah was heavily influenced by the works of African-American intellectuals like W.E.B. Du Bois and Marcus Garvey, as well as socialist thinkers such as Karl Marx and Vladimir Lenin.

Political Awakening and Return to Africa

While studying in the U.S., Nkrumah’s understanding of colonialism and his role in the global fight for racial equality sharpened. He became deeply involved in Pan-Africanist circles and started conceptualizing the liberation of Africa. His exposure to political activism in the United States—particularly through the efforts of the African-American civil rights movement—fueled his belief in African self-determination.

Kwame Nkrumah moved to London in 1945 to study at the London School of Economics and to deepen his Pan-Africanist activism. That same year, he co-organized the historic Fifth Pan-African Congress in Manchester with other prominent African and Caribbean leaders, including Jomo Kenyatta, W.E.B. Du Bois, and George Padmore. This congress emphasized the decolonization of Africa as well as the responsibility of the newly educated African elite to lead the continent’s struggles for independence.

Kwame Nkrumah’s time in London proved transformative. He worked closely with political activists from across Africa and participated in several anti-colonial campaigns. His growing prominence and radical approach brought him into contact with leaders on the continent and in the diaspora, cementing his reputation as a rising star in the Pan-African movement.

Leadership in Ghana’s Independence Movement

Kwame Nkrumah returned to the Gold Coast in 1947 at the invitation of the United Gold Coast Convention (UGCC), an organization primarily composed of elites striving for constitutional reforms under British colonial rule. Initially serving as the party’s General Secretary, Nkrumah quickly distinguished himself as a fiery orator and a populist leader who appealed to ordinary Ghanaians. He sought rapid and complete independence for the Gold Coast, a stance that sometimes clashed with the more conservative approach of other UGCC leaders.

In 1949, sensing the need for a mass-based political movement, Nkrumah broke away from the UGCC and founded the Convention People’s Party (CPP). The CPP’s motto, “Self-Government Now,” resonated deeply with the oppressed majority, giving the party broad popular appeal. Nkrumah’s commitment to street-level organizing, political education, and grassroots rallies shifted the momentum of the independence movement, and he became the face of Ghanaian nationalism.

However, his activism came at a steep price. In 1950, Nkrumah was arrested and imprisoned for inciting a series of boycotts and strikes over colonial policies, but his incarceration only boosted his popularity. In the 1951 general elections, the CPP won decisively, and Nkrumah, even while imprisoned, was elected as the leader of government business (a role similar to a prime minister). Upon his release from prison, he formally took office and continued working toward complete independence.

Ghana Becomes Independent

Ghana finally achieved independence from British rule on March 6, 1957, becoming the first sub-Saharan African country to do so. This historic achievement was celebrated not only in Ghana but across the African continent. Kwame Nkrumah declared, “Our independence is meaningless unless it is linked up with the total liberation of Africa.” With these words, he signaled his intention to lead not just Ghana, but the entire continent, toward freedom and unity.

Kwame Nkrumah was a trailblazer in advocating for economic independence, pan-African solidarity, and the rejection of neo-colonial exploitation. Among his early initiatives were the expansion of Ghana’s educational system, industrialization projects (such as the construction of the Akosombo Dam and the establishment of state-owned enterprises), and the diversification of the agricultural economy. Although his vision of modernization met with some success, these initiatives placed a significant strain on Ghana’s resources, leading to financial difficulties.

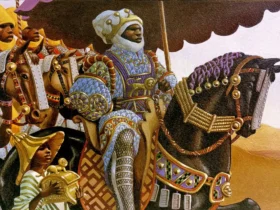

The Vision of Pan-Africanism

Beyond his role as a nationalist leader, Kwame Nkrumah’s broader mission was the liberation and unification of Africa. He firmly believed that the continent’s individual countries, many of them small and resource-constrained, could not genuinely thrive in a globalized world dominated by powerful Western nations. To counter this, he proposed the formation of a United States of Africa—a socialist federation that would pool resources, establish a common military, and promote continental self-reliance.

Kwame Nkrumah was instrumental in founding the Organization of African Unity (OAU) in 1963, which would later become the African Union (AU). The OAU, however, fell short of Nkrumah’s aspirations, as it opted for a loose association of sovereign states rather than full unity. Despite this, Nkrumah never abandoned his dream of African unity, and his writings—such as Africa Must Unite and Neo-Colonialism: The Last Stage of Imperialism—articulated a sharp critique of Western exploitation and a blueprint for a unified Africa.

Challenges and Downfall

Kwame Nkrumah’s rule wasn’t without controversy. Critics accused him of authoritarianism, as he centralized political power in the presidency and declared Ghana a one-party state in 1964. His government arrested political opponents and imposed restrictions on the press. Many Western governments, alarmed by his socialist leanings and close ties with the Eastern Bloc, worked to undermine him.

Meanwhile, Kwame Nkrumah’s ambitious economic policies ran into trouble. His industrialization projects, funded through foreign loans, led to mounting debt. Additionally, prices for Ghana’s cocoa exports—one of the country’s main sources of revenue—plummeted, causing economic instability. Public discontent grew, exacerbated by the perception that Nkrumah was more focused on Pan-African causes than Ghana’s immediate needs.

On February 24, 1966, while Nkrumah was on a peace mission to Vietnam, his government was overthrown in a military coup supported by Western intelligence agencies such as the CIA. This marked the end of his tenure in Ghana but not the end of his political relevance.

Life in Exile and Enduring Legacy

Kwame Nkrumah spent the remainder of his life in exile, first in Guinea, where he was granted asylum by President Ahmed Sékou Touré and was made honorary co-president, and later in Romania for medical treatment. He died of cancer on April 27, 1972, in Bucharest. His death marked the end of a troubled but extraordinarily influential life.

Kwame Nkrumah’s legacy is one of both triumph and cautionary lessons. He is celebrated as a liberator, a visionary, and one of the key architects of modern Africa. His concept of Pan-Africanism remains deeply embedded in African political thought, and the African Union continues to promote many of his ideals. However, his leadership also underscores the challenges of balancing national governance with larger ideological ambitions.

Conclusion

Kwame Nkrumah was more than a political leader; he was a symbol of hope, freedom, and unity for Africa. His fight against colonialism and his dream of a united Africa laid the groundwork for subsequent generations to pursue liberation and self-determination. While his ambitious vision of a “United States of Africa” remains unrealized, its essence continues to guide discussions on Africa’s future. Ghana’s independence, achieved under his leadership, remains a beacon of what is possible when a continent takes charge of its own destiny. Today, more than half a century after his passing, Kwame Nkrumah’s life and ideas stand as a reminder of the enduring strength of the African spirit and the quest for unity.

see also Who is Mobutu Sese Seko: The Powerfull Man Who Shaped Zaire